Written by Kim Beazley

Jan Hus planted seeds of faith which sprang forth in the Moravian prayer movement and continue to bear fruit today. It is a remarkable history of the movements of the Holy Spirit.

I don’t very often watch videos of lectures, interviews or similar presentations, especially if they’re more than seven or eight minutes long. My mind tends to wander, and I lose interest in anything longer.

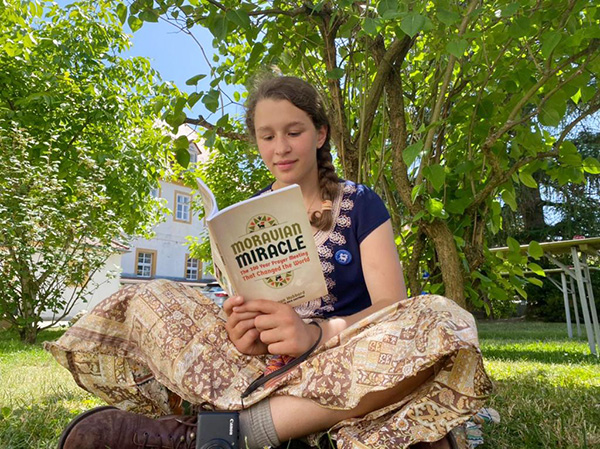

So imagine my amazement when I sat down to watch the video on a recent Canberra Declaration post, “The Moravian Brethren Movement: Emergence, Origins and Jan Hus’ Influence”, an interview Warwick Marsh had with Dr Jason Hubbard about his new book, “Moravian Miracle”. I was entranced the whole way through, stopping at intervals to take notes and find myself praying in the Spirit, with tears welling up!

Don’t you love it when the Holy Spirit sneaks up on you like that!

I did, though, have an interest in the subject matter, especially that of Jan Hus and the proto-Reformation Hussite Movement which followed his martyrdom. Also, as a lover of Classical music, I was aware of Hus’s influence on the emerging Nationalist movement in that part of the world where he lived, Bohemia (then an outer and neglected province of the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire), in the mid to late 19th century through two major figures, Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák.

My wife and I went on a European tour in 2019 which took us to Prague for three days, a trip we had always hoped to be able to do but always felt was beyond our budget, where there is a very prominent monument to Hus in the Old Town Square. What intrigues me about this is the fact that Czechia has always been almost entirely Catholic, though today it is the country in Europe with the least religious participation, a point made by our tour guide. But more of that later.

First, I want to give you a quick summary of the history dealt with in Warwick Marsh’s interview with Dr Hubbard.

As I mentioned, Hus was what could properly be described as a proto-Reformation figure, as his ideas were very similar to those espoused by Luther over a century later. Unlike Luther, however, Hus did not escape the Catholic Church’s punishment for his “heresy”, and he was captured, condemned, and burned at the stake in 1415.

When you watch the interview with Dr Hubbard, you will hear how Hus prophesied, before they lit the flames, that his message would not die, as his persecutors believed. Instead, it would be a “hidden seed” falling into the ground and dying for a season before one day sprouting again and bearing much fruit, giving a prophecy in that respect for a century in the future, which was clearly fulfilled in Martin Luther. He then cried out, “What I taught with my lips, I now seal with my blood.”

After Hus’ death, his followers revolted, and the most radical group settled on a hill not far from Prague and founded a new town, which they named Tabor after the biblical mountain of the same name. They were, thus, called Taborites. There followed twelve years of bloody struggle, known as the Hussite Wars.

For the purposes of this article, I will fast-forward through the reforms of Luther to the Moravians and their leader, Count Nikolaus von Zinzendorf, because it’s first of all the timing of their foundation, June 17th 1722, which is significant, as it’s 300 years ago today. This was the day that the first tree was felled for the first dwelling to be erected at their settlement, which they named Herrnhut (in English “the Lord’s watch”), which was inspired by Isaiah 62:6-7 —

“On your walls, Jerusalem,

I have appointed watchmen;

All day and all night they will never keep silent.

You who profess the Lord, take no rest for yourselves;

And give Him no rest until He establishes

And makes Jerusalem an object of praise on the earth.” (NASB)

Interestingly, too, Zinzendorf also referred to “hidden seeds”, the same phrase used by Hus three centuries before.

Dr Hubbard also mentioned a well that they dug there, and that they subsequently found the area contained numerous springs. The well they named Isaakbrunnen (in English “Isaac’s Well”), inspired by Genesis 26:18,

“Then Isaac dug again the wells of water which had been dug in the days of his father Abraham, for the Philistines had stopped them up after the death of Abraham; and he gave them the same names which his father had given them.” (NASB)

The core activity at Herrnhut was prayer, which continued unbroken for over a century. After ten years they began to send out missionaries, many decades before anyone else. Dr Hubbard mentions how the first Moravian missionaries went to the West Indies and evangelised and ministered to the slaves, some even selling themselves into slavery for the purpose! This causes me to wonder if these acts, along with the 24/7 prayer, created more “hidden seeds”.

Concurrent with the early years of this praying community, we also find in the British colonies along the Atlantic coast of North America what became known as “the First Great Awakening”, for which I can find no material or personal link to the Moravians, and the beginnings of which virtually coincide with the first Moravian missionaries.

Also, at around the same time, we find the early preaching of George Whitefield in England, and shortly after the beginning of the even more extraordinarily fruitful ministry of John Wesley, who was converted after being introduced to the Moravians.

Could these also be “hidden seeds” sprouting from those of Jan Hus?

But remember those Moravians ministering to the slaves? A later associate of Wesley’s is John Newton, the former slave trader whom God miraculously saved, both physically and spiritually, who wrote the most famous of all hymns, Amazing Grace. And a later associate of Newton’s was William Wilberforce, the politician whose persistence over many years led to the abolition of slavery across the British Empire.

This ongoing revival in the United States over several periods across the first half of the 19th century eventually led to the abolition of slavery in America as well, though of course not without that nation haemorrhaging so horribly due to their four-year Civil War.

Having now moved past the issues discussed by Warwick Marsh and Dr Hubbard, I believe it’s possible that these “hidden seeds” continued to sprout, and perhaps they still are.

I mentioned my love of classical music, and in the context of Bohemia and her struggles for, at least cultural recognition if not national independence, the two major figures, Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák. Just as with Hus, and even with Luther and Zinzendorf, there is also an element of nationalism that I believe that God is equally interested in, as all through Scripture there are references to tribes, languages, and nations. As we will see, that issue is with us still today, and perhaps even more so.

Both Smetana and Dvořák composed works that reflected the struggle for Bohemian culture, by writing music that was steeped in traditional Bohemian and Moravian idioms. And two of their best-known works are direct references to Jan Hus and the Hussites. Smetana composed a set of six Symphonic Poems on Bohemian nationalist themes, titled “Má vlast” (“My Fatherland”), the fifth bearing the title “Tabor”, the theme for the piece is quoted from the first two lines of the Hussite hymn, “Ktož jsú boží bojovníci” (“Ye Who Are Warriors of God”).

Dvořák’s was a concert overture titled “Hussite”, which is built on the same hymn tune.

Now fast-forward through the next century, where the Czechs gain their independence from one Empire after World War 1, only to fall under another as the first conquest of the Nazi Empire, only to be swallowed by another imperial power, Soviet Russia, after the fall of Nazi Germany.

But do those “hidden seeds”, mixing as they do God’s faithfulness to His prophets as well as His love for nations, still bear fruit today?

The fall of Communism bears that out, and in reference to our story, the music of those Bohemian masters come to light again, especially the Smetana piece, which was performed in Wenceslas Square in Prague by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of their conductor who had been living in exile in the West, Rafael Kubelík (it is from this performance that the video above is taken, where people can be seen sitting around the statue of Jan Hus on his memorial).

It’s also worth mentioning the fact that a Polish Catholic priest, Karol Wojtyła, who grew up near the border of the area Hus knew as Bohemia, became Pope John Paul II, who was also instrumental in the fall of the Soviet Empire.

Statue on Charles Bridge

But that’s not the end of my story. As I said at the beginning, my wife and I were in Prague almost three years ago, and this is where another figure, a contemporary of Jan Hus, enters the picture. He was a bishop named Johann Nepomuk, serving at the time of King Wenceslas IV (who could easily have been called “Bad King Wenceslas”!).

The story goes that Wenceslas suspected his wife of infidelity, and as Nepomuk was her confessor, he grilled the bishop to find out if she had said anything during Confession. But Nepomuk would not defile the sanctity of the Confessional, even under torture. So Wenceslas had him drowned in the Vltava River, thrown off the King Charles IV Bridge.

Today there is a memorial statue on that bridge. Close to the statue is another, at the point where he was thrown off, where passers-by are invited to make a wish, where the right hand should be put on the cross, and the left hand twice rubs Nepomuk’s image and the stars over his head, while the left foot is put on a nail on the pavement.

When our tour guide explained all of this, and after her previously explaining the “backslidden” nature of the whole nation, an idea came to me, which I believe was inspired. I didn’t rub the good bishop for luck, but I did place my hand in the required fashion on the cross, as well as my left foot on the nail in the pavement, and I prayed for the Holy Spirit to fall on Prague and the whole Czech nation.

So, am I allowed to wonder if my action was yet another tiny, though “hidden seed” going all the way back to Jan Hus? I certainly pray so.

Here we are, 300 years after the beginning of the mighty prayer and evangelism explosion of the Moravians, which was roughly 300 years after the death of Hus and the subsequent uprising which led to the expansion of his beliefs.

Is it time for another similar outpouring “for such a time as this”? I believe it is, but we need to be wise, and like the sons of Issachar, be “men who understood the times, with knowledge of what Israel should do” (1 Chronicles 12:32 NASB). And we may be about to pass through difficult times, just like all those predecessors have passed through.

Who knows what the future holds in respect to difficulties brought about by economic difficulties or even persecution, but like Hus, Luther, Zinzendorf and others, we know the One Who holds the future!

___

Photo by JJ Jordan.